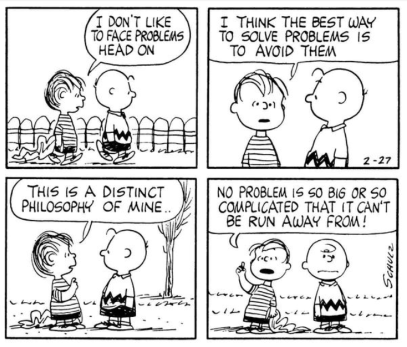

When we come across a major problem, we are all tempted to react like Linus. In the case of the EU restriction proposal for PVDF, it’s not going to help!

The EU has decided that the best way to tackle the scourge of fluorinated organics contaminating the environment is to eliminate all potential sources of the contamination. This means banning the manufacture and use of per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), and this includes PVDF. The EU definition of PFAS is clear (Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) – ECHA (europa.eu)) and the fact that PVDF is included as a PFAS has been confirmed by the European representative group for fluoropolymers, the FPP, Who we are – FPP4EU.

As pointed out in my previous blog, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in the US has tried to take a cautious and relatively business-friendly approach to PFAS and deemed that compounds are acceptable until toxicity data prove otherwise. Effectively compounds are ‘innocent until proven guilty’. In contrast, the EU is taking a precautionary approach prioritizing the environment and aiming to remove the whole class of PFAS compounds unless the benefits of retaining specific compounds, potentially in specific uses, outweigh the advantages of removal. This strategy could effectively be presented as, ‘guilty until proven innocent’. Both approaches seek to protect human health, but they are coming at the problem from perspectives which are polar opposites.

Should the definition of PFAS include PVDF? The EU restriction proposal for PFAS will be decided after the end of the current consultation period which concludes this September. Derogations may be granted for compounds deemed sufficiently beneficial or potentially irreplaceable. But the status quo will be that PVDF falls within the proposed restriction unless suppliers and users make a compelling case for it to be excluded.

Hollow fibre PVDF membrane manufacture is concentrated amongst relatively few suppliers. For the international market, the largest supplier of modules for membrane filtration applications is the Zenon factory based within the EU and the 2nd largest is the Memcor factory in Australia, a subsidiary of US owner Du Pont which has an extensive presence in the EU. Both companies will be profoundly impacted. Policy pronouncements in Europe will inevitably shape decisions in the US. And although alternatives are feasible for the European membrane market, the US has clearly been in love with PVDF membranes for the past 25 years.

PVDF is also used for MBR in both hollow fibre and flat sheet formats and this application would be strongly affected since PVDF is even more dominant here than in membrane filtration. Chinese manufacturers have a strong position in MBR and many products are made solely for use within their domestic market. Although the China local market might not be affected in the short term, the re-structuring of the world order will surely have an effect so Chinese companies should also be concerned.

Outside of these high profile uses, PVDF is used as a component for other membrane applications in water treatment, for example as a flat sheet support in spiral wound products. In terms of its technical performance, it would be irreplaceable or at the very least, hard to replace. Researchers and developers of the future will have a key tool removed from their armoury.

The industry needs to make its case to preserve PVDF membranes or make the case for a phased withdrawal, and it doesn’t have long to act. While membrane filtration could survive without PVDF, most people would agree that MBR couldn’t or would be severely curtailed. The problem is not going to go away. The fluoropolymer representative body (FPP) has issued a six point action plan (FPP4EU-Position-Paper-April-2023-final-1.pdf) and is calling for derogations in key applications which are not time limited. This is a big ask and will take solid persuasion to either prove that PVDF does no harm in the membrane context or at least have a defined plan to build the case. This could potentially be combined with a timeline or a planned and phased change to alternatives.

The other option is to fall off the edge of the cliff. For countries or applications committed to PVDF, the change could be devastating; an assault in one segment would have consequences everywhere. Denial and avoidance will hasten the end for PVDF. Engagement and negotiation are the only option.